“Read it with pleasure, and think about all the ways Asimov has changed the world.”

—Locus

No work of science fiction in this century has captured the imagination of so many readers as the epic future history put forth in the stories and novels of Isaac Asimov. In this newly revised volume, a select group of the Good Doctor’s fellow writers explore his astonishing creation from their own unique perspectives—and offer personal tributes to the late, great asimov some years after his death.

These writers are

FOUNDATION’S FRIENDS

Newly Revised and Expanded

Poul Anderson • Orson Scott Card • Hary Harrison • Mike Resnick • Robert Silverberg • Connie Willis

and a dozen others!

Plus a second preface by Ben Bova, and a second afterword by Janet Asimov!

“Bless you, Isaac. Bless you, Isaac’s children, found herein.”

—Ray Bradbury

Well, it’s nice to know that all those writers are newly revised and expanded.

This book was originally issued in 1989 in honor of the Good Doctor’s fiftieth anniversary as a professional writer and was reissued, after Asimov’s death, in 1997 with additional material. The idea was for Asimov’s friends and colleagues to write material involving him or his fictional universes, to show their affection and appreciation for him and his contributions to science fiction.

The original book started out with two introductions, one by Ray Bradbury (a respected colleague) and Ben Bova (a close friend). Bradbury’s piece is relatively weak and almost feels like a something tacked on because of Bradbury’s name, not his familiarity with Asimov’s work. Bova’s is quite good, noting that Asimov actually wrote more non-fiction than fiction, but that it was the fiction which has captured the imagination most. At the end of the original book are two afterwords, one by Janet and the other by Asimov himself.

Sandwiched between are seventeen pieces of fiction. They are:

“Strip-Runner,” by Pamela Sargent, a story set in New York just after the action of The Caves of Steel. A young girl has turned to strip-running as a way of dealing with the frustration she feels at the limited future lying before her. A legendary ex-strip-runner makes contact with her and steers her toward Elijah Baley’s group preparing to colonize other planets. Sargent is a solid sf writer and produces a good piece. It starts out well and utilizes Asimov’s universe well, but the ending is weak and too predictable.

“The Asenion Solution” by Robert Silverberg. This is a humorous piece which reminds one of nothing in Asimov’s oeuvre so much as the sadly underrated “The Holmes-Ginsbook Device.” As the title might suggest—“Asenion” being one of the more notorious misspellings of Asimov’s name to occur over the years—this is nothing but a series of inside jokes, starting with the mysterious appearance of Plutonium-186 in labs all around the earth, tying it to the notorious Silverberg-Asimov incident that inspired The Gods Themselves. Some of them I got, but a lot of them I didn’t. It isn’t bad, but I’m afraid it would likely be better if one were part of the inner circle of science fiction.

“Murder in the Urth Degree,” by Edward Wellen, a Wendell Urth mystery. Wellen is a writer with whose work I’m not familiar. It’s nice that somebody picked on the Urth stories for an homage, but this story doesn’t capture well the feel of that series, is sillier than the Urth stories Asimov wrote, and is in fact rather weak.

“Trantor Falls,” by Harry Turtledove, a story of the sack of Trantor by the barbarian warlord Gilmer mentioned in “The Mule.” Turtledove is a known name in sf and provides here one of the stronger stories in the book. There is little suspense, as anybody who’s read the original Foundation books can tell how it’s going to end, but the characters are solid and interesting anyway.

“Dilemma,” by Connie Willis. This is a hilarious little piece set in Asimov’s future as he hears the publication of his thousandth book (Asimov’s Guide to Asimov’s Guides). This story made it into Robots from Asimov’s, and I review it there. Suffice it to say that Willis is one of the best sf writers alive today who is able to write humor and drama equally well. This is one of the high points of the book for me.

“Maureen Birnbaum After Dark,” by the late George Alec Effinger, another well-known name in sf. Effinger wrote a series of pastiches of other authors’ works using the character of Maureen Birnbaum, an American Jewish princess mysteriously set off from one bizarre place to another with only her metallic underwear and broadsword to help her through. Effinger has published a collection of these stories, including this one, as Maureen Birnbaum, Barbarian Swordsperson. The stories are fun, and this not least of them. Definitely recommended.

“Balance,” by Mike Resnick, a story of Susan Calvin’s home life (after a fashion). Resnick is a good writer, but this is not the best he’s done and is on the weak side.

“The Present Eternal,” by Barry N. Malzberg, also a well-known sf writer. This is the story of the aftermath to “The Dead Past,” one of my favorites by Asimov. It rather feels like Ted Sturgeon’s story on the same sort of topic, what life was like after a new invention made the past visible to anyone. The story is not bad on its own merits, but doesn’t measure up to the original.

“PAPPI,” by Sheila Finch, whom I do not know. This is a Susan Calvin/Stephen Byerley story of sorts, centered around Calvin’s former office-mate and her son. Finch is an author whose work I do not know at all. Her piece suffers most because of the company it keeps.

“The Reunion at the Mile-High,” by Fred Pohl, who should need no introduction to the Asimov fan. Pohl has here written an alternate history story involving the Futurians, the fan club to which Asimov briefly belonged in the late 1930’s, which contained many of the most famous names of science fiction’s Golden Age. It’s a beautiful nostalgia piece, written by a man who regards his colleagues highly and remembers keenly the days when science fiction still hadn’t become real.

“Plato’s Cave,” by the late Poul Anderson. Anderson is one of the best writers of sf of the past half century but is strangely not nearly as well-known as he deserves. This is a Powell and Donavan story, set among Jupiter’s moons. The plot is not easy to explain except to say that Powell and Donavan need to prove to a recalcitrant robot whom they cannot approach directly that they are, indeed, human beings. This isn’t quite as good as Asimov’s original Powell and Donavan stories but is quite good. The worst thing about it is probably that it feels like an Anderson story set in Asimov’s world, almost always a jarring experience.

“Foundation’s Conscience,” by George Zebrowski, a known sf writer but not one of the first tier. This is a story of a researcher prying in to the series of Seldon’s recorded messages for the First Foundation. This one just doesn’t work for me.

“Carhunters of the Concrete Prairie,” by the late, great Robert Sheckley. This is only loosely related to Asimov and is very strange, but what else would one expect from Sheckley? It’s not bad, but certainly not Sheckley’s best or what one might find in a book of the Good Doctor’s stories.

“The Overheard Conversation,” by the late Edward D. Hoch, the lone mystery writer in the book. This is a Black Widowers mystery, but not bad and nicely close to Asimov’s Black Widowers, even if not up to the quality of the better stories in the series.

“Blot,” by the late Hal Clement, a robot story. Clement is well-known as an sf writer and his story here isn’t half bad but is only poorly connected to Asimovia.

“The Fourth Law of Robotics,” by Harry Harrison, a very well-known writer. This is a Susan Calvin story but tends to remind one of the Asimov silly short “First Law.” Perhaps that similarity tends to bring it down a notch or two.

“The Originist,” by Orson Scott Card. I’m going to talk about this one a bit.

Card is one of the top writers in sf today and has here written easily the strongest story in the book. Although it’s set on Trantor as Harry Seldon is setting up the Second Foundation, it is not at all an “Asimov” story, as it is about the feelings of loss experienced by a brilliant and fabulously wealthy scholar, Leyel Forska, as his world seems to degenerate around him. Seldon, despite a close friendship, rejects him for participation in the Encyclopedia Galactica project. His wife seems to have lost interest in him in favor of new friends she’s made in the Imperial Library. The Empire takes away his wealth.

This is a story about people and emotions, not at all the kind of thing Asimov would write. It is also a story about community formation though the medium of story-telling. Card is a Mormon (as am I), and his Mormonism shows through here. Mormonism has an exceptionally strong sense of community, and that community is reinforced through a number of techniques including story-telling. Indeed, there is a hot debate within the more intellectual fringes of the Mormon community as to whether such stories derive their value from their historicity or independent of it.

At the same time, then, “The Originist” is both an interesting short story from a strong writer and an insight into Card’s own psyche.

Few of the stories in this book could ever stand on their own; they could hardly be found anywhere but in a book honoring Asimov. (Effinger’s story is, of course, an exception.) Most Asimov fans do not rate the book highly; personally I think it’s quite good, and better than Gregory Benford’s Foundation’s Fear, for example. It’s worth finding and picking up for the original material alone.

The additional material for the second edition consists of three Asimov stories which he rated highly himself (“The Immortal Bard,” “The Last Question,” and “The Ugly Little Boy”) and a series of tributes to Asimov originally published in Asimov’s Science Fiction shortly after the Good Doctor’s death. Those of us who remember the Good Doctor’s death all too keenly have a chance to review our own emotions as we work through these tributes. They only add to the overall value of the book.

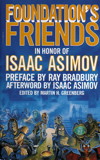

One final note: The cover consists of a portrait of a number of robots sitting about in a bar, their faces based on those of the authors of the stories in the book. Unfortunately, only Asimov himself and Silverberg do I recognize for sure. It would be a nicer feature of the book if one knew who the others were.