Here is a bonanza for Asimov fans—a highly selective, amusing, informative, wide-ranging, beguiling, and totally Asimovian anthology of his favorite passages from his second hundred books! Incredible as it may seem, a similar harvest from his first hundred books was published scarcely a decade earlier and received a joyous welcome from his many admirers.

Like Opus 100, the book is divided into subject categories covering such topics as Astronomy, Biology, Chemistry, History, Humor, Literature, Physics, and Words—there is no end to the variety of Isaac’s enthusiasms—drawn from his serious scientific books, novels, essays, short stories, children’s books, and annotations of the classics. Each selection is accompanied by comments, filled with autobiographical nuggets, explaining how he came to write it and why he included it.

Unfortunately, although there are hundreds of thousands of Asimov fans spread all over the world, there is only one Isaac Asimov and he lives in New York City. However, for anyone who hasn’t had the pleasure of knowing Isaac himself, this highly personal and ebullient anthology is the next best thing.

And as he says himself, “Nobody who reads my writings, after all, his very likely to have read all my books, or even most of them; and many people who do read and are, presumably, fond of some of my books are not aware of some of the other kinds of writing I do.”

So here is Isaac Asimov face to face, radiating wit, wisdom, and ready to share with you his insatiable enthusiasm for life in all its variety.

Opus 200 isn’t as good as Opus 100. (Of course, it’s still better than Opus 300, which is something, I suppose.)

Of course, this is largely Golden Age Syndrome talking here. I read Opus 100 because I was referred to it by Asimov himself; I read Opus 200 because I saw it in the bookstores six years later when my own personal “golden age” had long ended.

On the other hand, I think there is something objective here. The fact is that Asimov’s second hundred are less impressive than his first. Among Asimov’s first hundred are his early (and best) science fiction books: Foundation, I, Robot, The Caves of Steel, The End of Eternity, and so on. We have the early science books that made his reputation as a writer of non-fiction: Inside the Atom, The Chemicals of Life, The Clock We Live On, The Search for the Elements. We have the early editions of his major non-fiction works: The Intelligent Man’s Guide to Science, Asimov’s Biographical Encyclopedia of Science and Technology. We have the first six F&SF essay collections: Fact and Fancy, and so on. We have the earliest (and best) Houghton-Mifflin histories: The Greeks: A Great Adventure, The Roman Republic, and The Roman Empire. We have several of his best and longest-lived science non-fiction: Understanding Physics, The Universe, Life and Energy, Photosynthesis, The Noble Gases. We have virtually all of his “word” books: Words of Science, and so on. We have Asimov’s Guide to the Bible, volume one and Asimov’s Guide to the Bible, volume two.

In short, we have most of his most memorable works, and a remarkably high percentage of them are still in print, forty to sixty years later.

And in the second hundred? Well, we do have some major and important works: Asimov’s Guide to Shakespeare, volume one and Asimov’s Guide to Shakespeare, volume two. Eleven F&SF essay collections (although four of them are recyclings such as Asimov on Astronomy). Top-notch science fiction: The Gods Themselves. Solid histories: Constantinople, the Forgotten Empire. Funny books: The Sensuous Dirty Old Man, Isaac Asimov’s Treasury of Humor. Anthologies like The Early Asimov. The first Black Widower mysteries (Tales of the Black Widowers). Solid science: Jupiter, the Largest Planet, The Ends of the Earth. And so on.

Unfortunately, we also have some less memorable books. Juvenile science books are represented here by the ABC books (which are largely failures) such as ABC’s of Space, and by the first “How Did We Find Out” books, which are good but slight. We’ve also got all five Ginn science program books, which Asimov himself loathed. We have several limerick books (Lecherous Limericks, Asimov’s Sherlockian Limericks), which are vaguely funny but also vaguely disappointing. We have anthologies of Asimov’s weaker stories which are being anthologized for the sake of completeness and not value (Buy Jupiter and Other Stories). We have the later and weaker histories which did so poorly that Houghton-Mifflin brought the series to an end (The Golden Door). We have the first of the myriad sf anthologies co-edited with Marty Greenberg which would come to dominate Asimov’s publishing. And so on.

In short, although we have some of Asimov’s best stuff in his second hundred, as we did in his first, we have less of it, and we have a much lower excellent-to-OK ratio. And, I'm willing to bet, a smaller percentage of his second hundred books are currently in print, although they are much, much younger.

As for Opus 200 itself, it reflects this. Asimov adds four new sections onto the eleven inherited from Opus 100 to reflect the wider diversity of topics he covers. He is a little apologetic in some sections about how his output has dropped in those topics. On chemistry, for example, he published no new full-length books in his second hundred, and so as an example of his writing on chemistry, he includes the science fiction story Good Taste. (I do love this story, but its inclusion here means that he is quoting the entire book inside this book! This is something which would occur later when some of Asimov’s shorter stories were published as books in their own right: Robbie, Sally, It’s Such a Beautiful Day, and so on, but this is the only case I'm aware of when he published the short story as a “book” first and then anthologized it. There is a precedent for longer works, given the inclusion of The Caves of Steel and The Naked Sun inside The Rest of the Robots.)

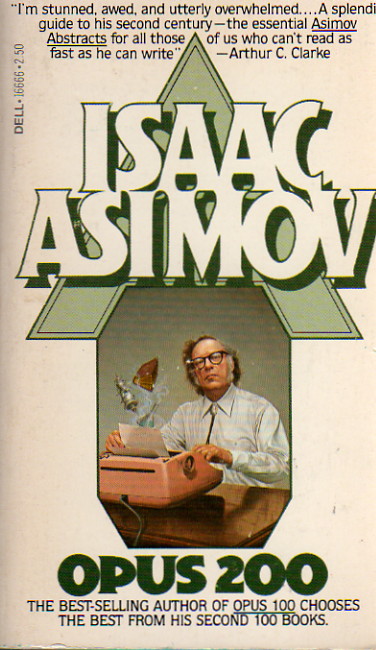

Except for the heavy inclusion of limericks—which I have never found as funny as did Asimov himself—the selections here do provide a good overview of the best he did in the 1970’s, and I would continue to recommend the book to an Asimov fan. It is is faulty, it is faulty only in comparison to Opus 100. And, if nothing else, the cover art—a picture of Asimov sitting on a throne made entirely of his published work—is worth almost any price.

Contents

|

“The Bicentennial Man” |

|

“Good Taste” |

|

“Light Verse” |

|

“Earthset and Evening Star” |

|

“The Thirteenth Day of Christmas” |